Research Backed Ways to Help Struggling Writers

/In a previous post, I talked about some of the similarities I’ve noticed in working with struggling writers. Now I’d like to share some methods for working with struggling writers that I’ve learned from personal experience and from the research on effective methods to improve student writing.

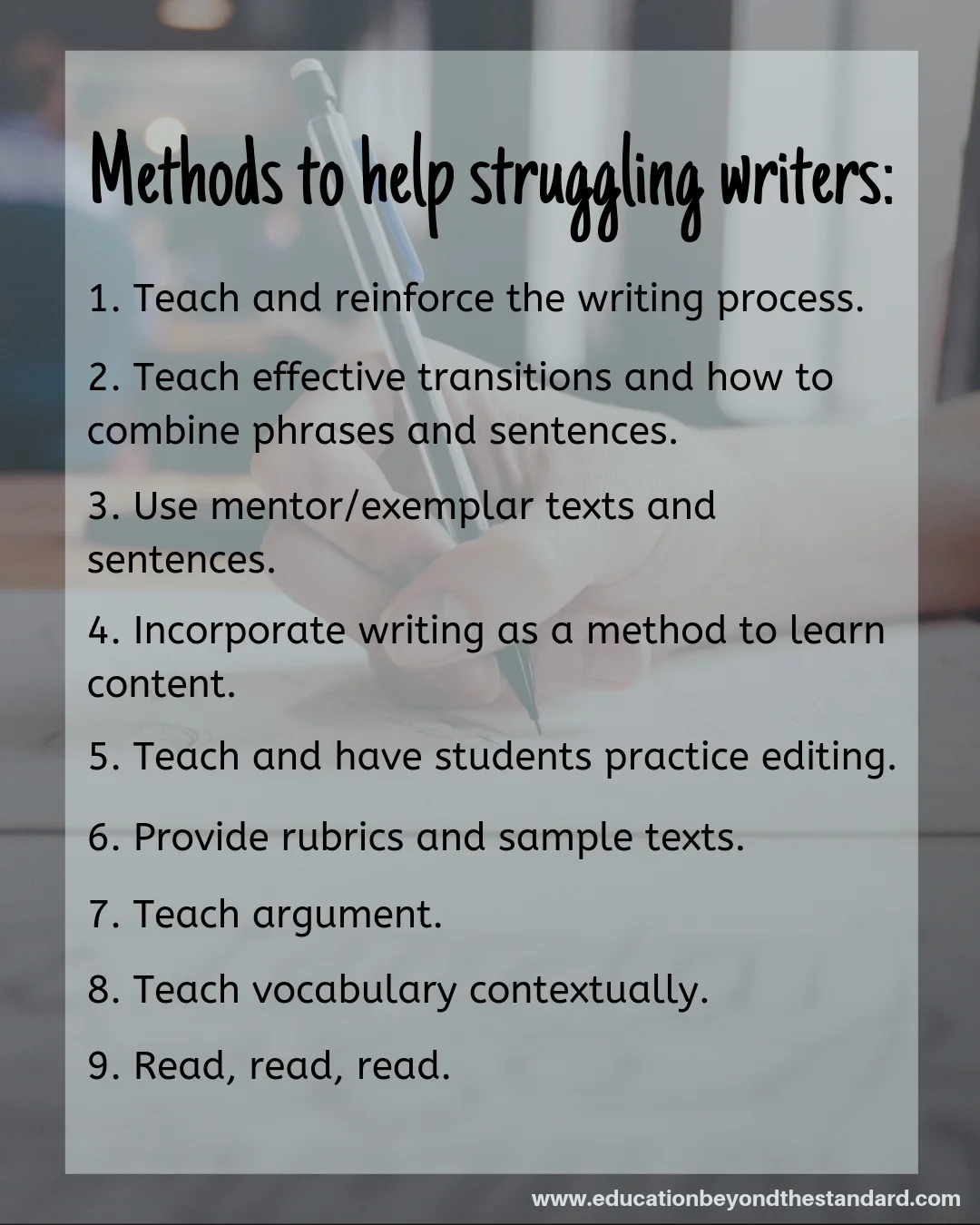

Teach and Reinforce the Writing Process

This point can’t be emphasized enough. While some stellar writers may instinctively use an effective writing process, the vast majority of our students will need specific instruction. Beyond teaching the steps of the writing process (Prewriting, Writing, Revising, Editing, Sharing), we need to teach students how to execute each step. And this requires practice.

Consider having students regularly outline essays in response to prompts in order to practice Prewriting. Make sure the outlines follow a logical structure and contain sufficient detail, as opposed to just brainstorming (which can be fine as an initial step in the Prewriting stage). Editing tasks and peer editing are good practice for editing and revising students’ own work.

Teach Effective Transitions and How to Combine Sentences

Struggling writers often have difficulty putting together pieces of information (or arguments and supporting facts) in a logical and coherent way. Specific instruction on transition/linking words and phrases and how to use them is crucial to helping student writers.

Use Mentor/Exemplar Texts and Sentences

Mentor texts and sentences illustrate the principles of writing and grammar that we’re teaching. Mentor sentences can be a great way to teach grammatical concepts and effective transitions. Also consider providing exemplar texts when you give a rubric (see below).

Incorporate Writing as a Method to Learn Content

Writing about recently learned content has repeatedly been found effective in increasing retention and understanding. I’m a big believer in bringing writing activities into all subject areas, including math, science, and social studies.

Writing can be used across subject areas to:

reinforce content (“explain,” “summarize,” etc.),

make connections (“how is this material connected to [current events, something we learned previously]?” etc.), and

engage critical thinking (“why is this relevant/important?” “what else can we learn about this topic?” etc.).

Having tutored students in math for many years, I’ve noticed that when students can summarize or explain a process in writing they almost always achieve mastery with that topic. Incorporating writing wherever we can and across subject areas increases content understanding and provides even more opportunities for writing practice.

Teach and Have Students Practice Editing

I can’t count the number of times I asked a student to edit his or her own draft, only to have the exact same draft returned to me with a few minor errors corrected. It took time for me to realize that many struggling writers don’t know intuitively how to edit their own work (or the work of others). Editing, just like writing, is a skill that must be taught. Students need to learn what to look for and how to look for it, as well as how to fix problems with sentences, paragraphs, or whole pieces of writing.

One of the best ways I’ve found to teach editing is by having students practice editing a text with defined numbers and categories of errors. By telling students how many errors there are within a certain category (like punctuation, verb tenses, etc.), we are training them to focus on the details that they otherwise may have skipped over. While zooming in to the grammatical details is important, we also need to teach students to zoom out to the big picture (the structure, strength of argument and supporting facts, etc.). Mentor texts are a great way to illustrate “big picture” qualities of writing.

Specifically Identify Writing Assignment Expectations (Rubric + Sample Texts) and Grade/Provide Feedback Accordingly

One of the many great things I learned while tutoring students for the SAT/ACT was the value of sample texts in addition to a rubric. Many of the SAT/ACT study books contain sample student essays with a given score according to the general rubric provided. Reading a high-scoring essay and a low-scoring essay with the rubric as the backdrop is an impactful way for students to understand a grading rubric.

All too often, students eyes’ glaze over while reading rubric measures such as “arguments and supporting evidence are presented cohesively.” Providing sample essays on the highest and lowest end of the rubric and requiring students to read them (or even better, reviewing and discussing them in class) is a powerful tool to help students understand what constitutes a great piece of writing.

Teach Argument

Argument and persuasion are often confused, but they are actually quite different. Argument can serve as persuasion, but persuasion requires much less in terms of reasoning. Argument is rooted in fact and logic while persuasion is rooted in opinion and emotion. Argument is essentially a truth-seeking endeavor, while persuasion is focused on, well, persuading.

I believe that we should prioritize teaching argument over persuasion, and that argument should be made a much bigger part of all school subjects. The process of argument (gathering evidence, making a claim, connecting the claim to the evidence, examining evidence to the contrary, and refining the claim accordingly) develops critical thinking and logical reasoning skills, which are part and parcel of thoughtful, coherent writing. These skills are also extremely important outside of academics.

Teach Vocabulary

While struggling writers often lack a broad vocabulary (or frequently misuse words), great writers tend to have great vocabulary and make effective word choices. Far beyond memorization of definitions, teaching vocabulary with a language building approach can have a great impact on students’ writing skills.

Vocabulary study with a language building approach is a holistic process that not only enriches students’ writing with greater variety of word choice, but also improves their grammar and their contextual understanding of language. Students learn words in context and practice using them correctly while also practicing good grammar. They learn to use different word forms (ex: meticulous, meticulously, meticulousness) while developing a better understanding of sentence structure.

Read, Read, Read

Studies have consistently supported a correlation between increased reading and better writing skills. The same goes for the link between reading and vocabulary and other cognitive skills. There is no question that reading provides great intellectual and emotional benefits, so the more we can have students read the better.

Outside of assigned reading, here are some ideas for encouraging and incentivizing student reading:

1) give an optional reading list (during the year and/or over breaks) with prizes for completion

2) set up a “Twitter style reading board” where students add “tweets” about the books they’re reading

3) host a student book club or create small group book clubs that select a book and meet once a month

4) hold a class reading contest or class vs. class contest

5) give an optional reading list from which students choose several books and complete book projects

6) maintain a classroom library with a diverse selection of fiction and nonfiction

7) allow in-class reading of student selected books when students complete class work

8) create an Instagram-style board where students post photos inspired by what they’re reading with captions that relate the image to the text

9) hold a “books made into movies” seminar—students read/watch and discuss which version was better

I’d love to hear what methods you’ve found effective in helping students improve their writing skills!