The Most Powerful Practice for Academic Growth

/Help students develop a growth mindset with a few simple steps.

Read MoreHelp students develop a growth mindset with a few simple steps.

Read MoreAs I went into my first year of teaching, I was far too overwhelmed to think about how I could consciously create a classroom culture. I did instinctively know that I wanted to establish an environment of trust, respect, and kindness, in line with my core values. But how to accomplish that?

As a more experienced teacher, I can now reflect a bit more on what a positive secondary classroom culture looks like and how we can build it. I also realize now that it’s not as hard as it may seem when you’re new to the classroom.

So what does a positive classroom culture look like? I define it as one that supports and enhances students’ learning, helps students take on challenges with a growth mindset, and promotes healthy social behaviors.

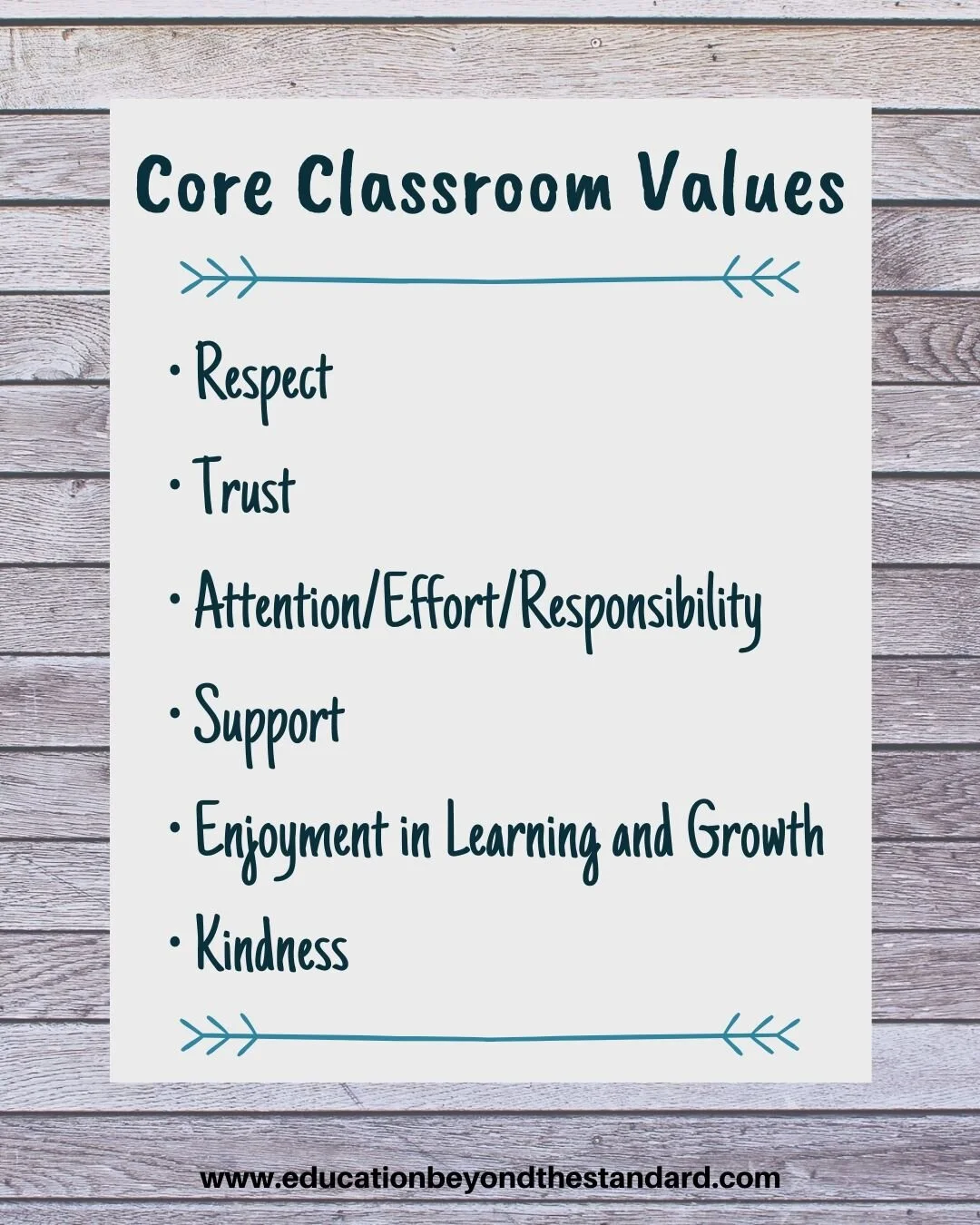

I think the first step in creating a positive classroom culture is getting to know our core values so we can be conscious about establishing classroom procedures, guidelines, and expectations that reflect them. What are some core values for the classroom that resonate with you? Here are a few of mine:

Respect

Trust

Attention/effort/responsibility

Support

Enjoyment in learning and growth

Kindness

Since I’m no longer in the classroom but still working with students as a tutor, I hear a lot about classroom cultures and management styles from students’ perspectives. Here are a few pieces of insight that I’ve gained from this experience:

Regardless of classroom management style, students can always sense (and always appreciate) when teachers truly care and are passionate about teaching.

Core classroom values such as trust, respect, and support start with teachers. Teachers who model these core values even in the face of behavioral issues lay the foundation for them to flourish in the classroom.

Consistently praising effort and improvement over perfection or traits like intelligence creates a supportive environment in which all students feel they can grow.

Clarity and consistency in the application of classroom rules and procedures helps to build a safe environment in which trust can develop.

Secondary teachers have the unique opportunity to “reset” students’ expectations about what a classroom experience can be. At the secondary level, kids are coming into the classroom with a wider variety of previous experiences in school, both good and bad. This means a greater variety of attitudes toward learning and ideas about appropriate classroom behavior.

With your core values and some student insights in mind, here are some thoughts for creating a positive secondary classroom culture, either from day one or to reset after a rocky period.

Communicate with clarity, warmth, and calmness what your expectations are. By communicating in this manner, you are modeling respectful, appropriate interactions and setting the standard for how you expect students to communicate in your classroom.

Put classroom rules, policies, and procedures in writing. You may even have students participate in the process of creating clear and fair policies.

Discuss the core values that you’ve identified and what they look like in action. Ask students to give examples of what each of the values looks like in action.

Provide clear, written academic expectations and policies, including late work, test retakes, extra help, and missed classes. Some of the most common issues I see with students I tutor involve these topics. You can avoid future confusion and disputes by clearly defining policies and students’ responsibilities from the beginning.

Have students sign all written policies and procedures to indicate they are in agreement with them.

If an issue arises that requires a change in classroom policies/procedures, discuss openly and clearly with students. As long as there is a clear rationale for the change, students will usually be on board.

Be authentic with students—if you make a mistake, acknowledge it. If a lesson or activity doesn’t go well, discuss it. Students don’t expect teachers to be perfect, and mistakes or bombed lessons can be a great opportunity for us to model accountability and authenticity.

Please let me know in the comments below if you have any tips or techniques for building a positive classroom culture at the secondary level!

Secondary curriculum in most schools and districts is meant to prepare students for university study, but it rarely prepares them for the exams that still play an important role in college admissions. Whether due to time constraints, the perceived difficulty of the material, or the idea that SAT/ACT material is incompatible with other curriculum priorities, SAT/ACT practice is often left to students to do on their own.

In this article, I’ll give you 5 reasons why incorporating SAT/ACT practice into your curriculum is a great idea, whether or not your school separately offers SAT/ACT prep courses or workshops. In a later post, I’ll give you some ideas for easy ways to do so.

When compared with the Common Core and other state standards, the SAT and ACT require a higher level of reading, language, and math skills. Not every topic or skill you teach will appear on the SAT/ACT, but where there’s an overlap, SAT/ACT questions generally go deeper and require more critical thinking and analytical skills. The reading passages are rich sources of academic and Tier 2 vocabulary. Math questions tend to require greater integration of diverse math skills and more complex problem solving.

Before I started tutoring and offering small group SAT/ACT test prep, I mistakenly believed that the SAT and ACT measured mastery of topics and content knowledge. As I began to understand the tests better, I realized that they are actually designed to measure academic skill.

While content knowledge is certainly a big part of doing well on the math portion of these exams, and vocabulary is important for the language portions, content knowledge only gets students so far. The rest comes down to skill: how well do students parse a text for meaning, argument, evidence, and structure? How well can they problem solve? How well do they think and write about a topic? These are skills that are crucial for students’ future academic outcomes.

All students are subjected to the same test, but unfortunately study after study confirms that socioeconomic factors play a major role in SAT/ACT scores. Building in some SAT/ACT-type practice to your curriculum is a great way to make sure all students gain familiarity with the test material and format.

I can personally attest to the truth of this one: when I mention to students that a particular math topic is tested frequently on the SAT/ACT, their ears perk up. What may have quickly been forgotten after a lesson or unit ends is now given a place of greater importance and is more likely to be remembered. Not every student will be motivated to pay extra attention to material they know might appear on the SAT/ACT, but many will.

For consistent early finishers and high achieving students, SAT/ACT practice provides a challenge and an opportunity to test and improve their skills. I love reinforcing crucial academic skills that are relevant to the topic at hand with “SAT/ACT challenge questions.”

I’m a big believer in the idea that all students (not just our self-motivated high achievers) benefit from challenging work that requires higher level thinking and problem solving, with the appropriate support and resources.

Please let me know your thoughts (and whether you include any SAT/ACT practice in your classroom) in the comments below!

Language building involves forming as many connections in the brain as possible so that new words are understood in concert with other words, ideas, and even visual representations.

Read MoreAs someone in an “ally” position as opposed to a perceived authoritarian, I’ve also been able to gain some insight into students’ motivations, their perspectives on school, teachers, assignments, etc., and their perception of themselves as students.

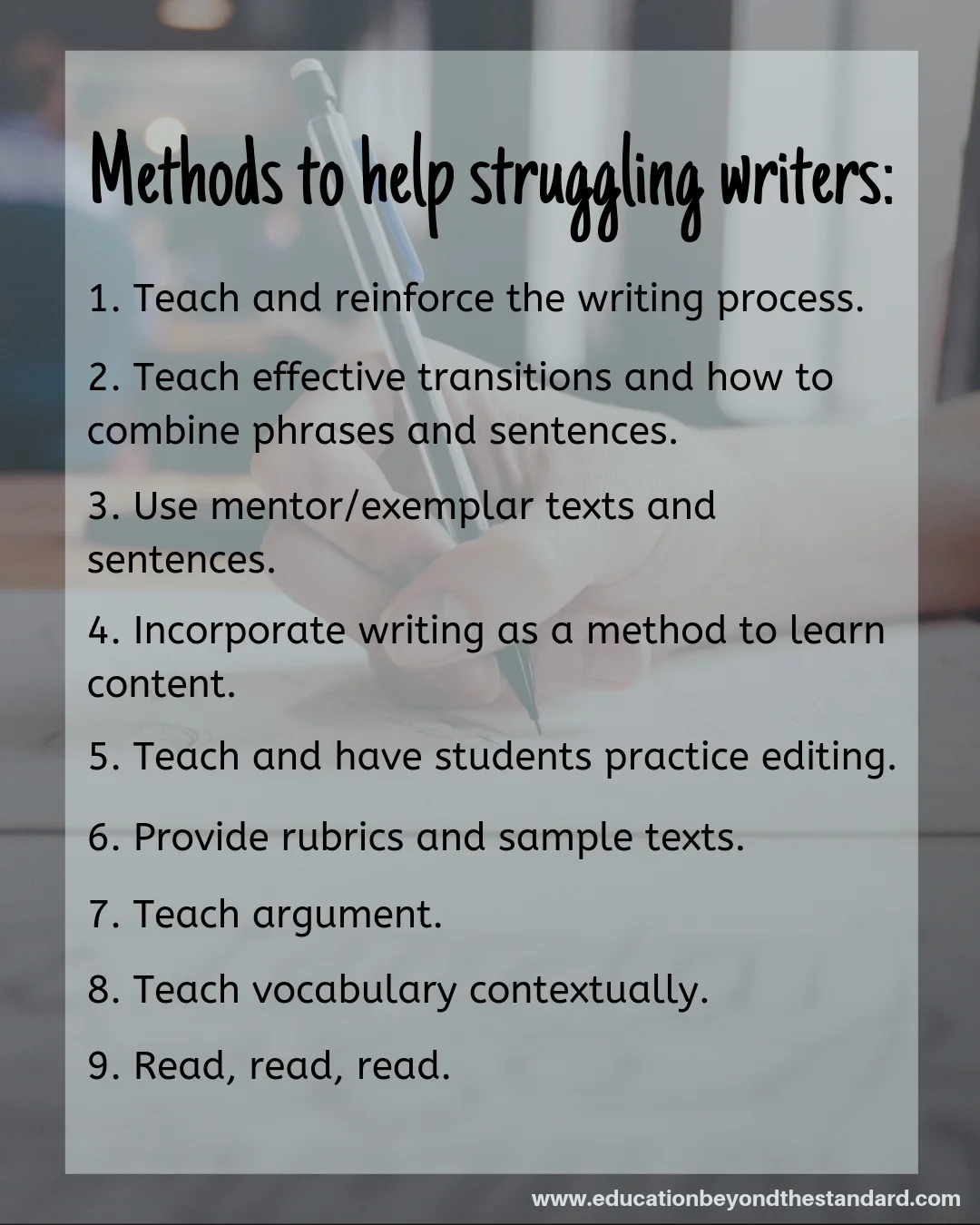

Read MoreIn a previous post, I talked about some of the similarities I’ve noticed in working with struggling writers. Now I’d like to share some methods for working with struggling writers that I’ve learned from personal experience and from the research on effective methods to improve student writing.

This point can’t be emphasized enough. While some stellar writers may instinctively use an effective writing process, the vast majority of our students will need specific instruction. Beyond teaching the steps of the writing process (Prewriting, Writing, Revising, Editing, Sharing), we need to teach students how to execute each step. And this requires practice.

Consider having students regularly outline essays in response to prompts in order to practice Prewriting. Make sure the outlines follow a logical structure and contain sufficient detail, as opposed to just brainstorming (which can be fine as an initial step in the Prewriting stage). Editing tasks and peer editing are good practice for editing and revising students’ own work.

Struggling writers often have difficulty putting together pieces of information (or arguments and supporting facts) in a logical and coherent way. Specific instruction on transition/linking words and phrases and how to use them is crucial to helping student writers.

Mentor texts and sentences illustrate the principles of writing and grammar that we’re teaching. Mentor sentences can be a great way to teach grammatical concepts and effective transitions. Also consider providing exemplar texts when you give a rubric (see below).

Writing about recently learned content has repeatedly been found effective in increasing retention and understanding. I’m a big believer in bringing writing activities into all subject areas, including math, science, and social studies.

Writing can be used across subject areas to:

reinforce content (“explain,” “summarize,” etc.),

make connections (“how is this material connected to [current events, something we learned previously]?” etc.), and

engage critical thinking (“why is this relevant/important?” “what else can we learn about this topic?” etc.).

Having tutored students in math for many years, I’ve noticed that when students can summarize or explain a process in writing they almost always achieve mastery with that topic. Incorporating writing wherever we can and across subject areas increases content understanding and provides even more opportunities for writing practice.

I can’t count the number of times I asked a student to edit his or her own draft, only to have the exact same draft returned to me with a few minor errors corrected. It took time for me to realize that many struggling writers don’t know intuitively how to edit their own work (or the work of others). Editing, just like writing, is a skill that must be taught. Students need to learn what to look for and how to look for it, as well as how to fix problems with sentences, paragraphs, or whole pieces of writing.

One of the best ways I’ve found to teach editing is by having students practice editing a text with defined numbers and categories of errors. By telling students how many errors there are within a certain category (like punctuation, verb tenses, etc.), we are training them to focus on the details that they otherwise may have skipped over. While zooming in to the grammatical details is important, we also need to teach students to zoom out to the big picture (the structure, strength of argument and supporting facts, etc.). Mentor texts are a great way to illustrate “big picture” qualities of writing.

One of the many great things I learned while tutoring students for the SAT/ACT was the value of sample texts in addition to a rubric. Many of the SAT/ACT study books contain sample student essays with a given score according to the general rubric provided. Reading a high-scoring essay and a low-scoring essay with the rubric as the backdrop is an impactful way for students to understand a grading rubric.

All too often, students eyes’ glaze over while reading rubric measures such as “arguments and supporting evidence are presented cohesively.” Providing sample essays on the highest and lowest end of the rubric and requiring students to read them (or even better, reviewing and discussing them in class) is a powerful tool to help students understand what constitutes a great piece of writing.

Argument and persuasion are often confused, but they are actually quite different. Argument can serve as persuasion, but persuasion requires much less in terms of reasoning. Argument is rooted in fact and logic while persuasion is rooted in opinion and emotion. Argument is essentially a truth-seeking endeavor, while persuasion is focused on, well, persuading.

I believe that we should prioritize teaching argument over persuasion, and that argument should be made a much bigger part of all school subjects. The process of argument (gathering evidence, making a claim, connecting the claim to the evidence, examining evidence to the contrary, and refining the claim accordingly) develops critical thinking and logical reasoning skills, which are part and parcel of thoughtful, coherent writing. These skills are also extremely important outside of academics.

While struggling writers often lack a broad vocabulary (or frequently misuse words), great writers tend to have great vocabulary and make effective word choices. Far beyond memorization of definitions, teaching vocabulary with a language building approach can have a great impact on students’ writing skills.

Vocabulary study with a language building approach is a holistic process that not only enriches students’ writing with greater variety of word choice, but also improves their grammar and their contextual understanding of language. Students learn words in context and practice using them correctly while also practicing good grammar. They learn to use different word forms (ex: meticulous, meticulously, meticulousness) while developing a better understanding of sentence structure.

Studies have consistently supported a correlation between increased reading and better writing skills. The same goes for the link between reading and vocabulary and other cognitive skills. There is no question that reading provides great intellectual and emotional benefits, so the more we can have students read the better.

Outside of assigned reading, here are some ideas for encouraging and incentivizing student reading:

1) give an optional reading list (during the year and/or over breaks) with prizes for completion

2) set up a “Twitter style reading board” where students add “tweets” about the books they’re reading

3) host a student book club or create small group book clubs that select a book and meet once a month

4) hold a class reading contest or class vs. class contest

5) give an optional reading list from which students choose several books and complete book projects

6) maintain a classroom library with a diverse selection of fiction and nonfiction

7) allow in-class reading of student selected books when students complete class work

8) create an Instagram-style board where students post photos inspired by what they’re reading with captions that relate the image to the text

9) hold a “books made into movies” seminar—students read/watch and discuss which version was better

I’d love to hear what methods you’ve found effective in helping students improve their writing skills!

Novel or nonfiction study is a great way to teach so many things: themes and symbolism, author’s craft and devices, literary analysis, and vocabulary too. But all too often, vocabulary gets relegated to a list with definitions that students memorize for a quiz or test...and likely forget soon after. Fortunately, it’s fairly easy to incorporate new vocabulary and language building activities into a novel or nonfiction study unit.

Read More

Powered by Squarespace.