The Most Powerful Practice for Academic Growth

/Help students develop a growth mindset with a few simple steps.

Read MoreHelp students develop a growth mindset with a few simple steps.

Read MoreAs teachers, we have quite a bit of control over how we teach topics to our students, the activities we give them to enhance learning, and the preparation materials we give out before unit tests, midterms, etc. But we don’t have much control over what students do with what we give them as soon as they leave class for the day (and sometimes even in our rooms). Some students seem to know instinctively how to assimilate the new information and skills they learn in class, while others have parents who give them helpful study tips and fill in any blanks in their understanding. But unfortunately, others leave class confused about the topics covered and lack the tools (or the sense of agency) to improve their understanding.

While teaching learning strategies is often left to the realm of special education, in my experience most students benefit from gaining some insight into their own learning habits and practices. In fact, I think teaching kids how to learn is equally if not more important as teaching them what to learn. As a former classroom teacher turned tutor, I’ve realized that by giving kids insight into their own learning process we are setting them up to be able to approach future material confidently and to learn it successfully throughout their lives.

My goal in tutoring is to help students develop skills and habits that eventually make tutoring unnecessary, and I’ve found that one of the most powerful ways to do that is by getting them into the practice of being self reflective about their own learning. And it doesn’t take much in the way of formal teaching; with a series of questions and mostly student-driven discussions students become much more conscious of their approach to learning and about specific strategies that they can use to learn more effectively.

Clearly, one-on-one discussions with students are a great way to help them reflect on their learning, but unfortunately the classroom setting doesn’t give us much one-on-one time. I wanted to find a way to bring this beneficial practice into the classroom, so I’ve created this no-prep student self-evaluation that teachers can use and reuse throughout the year to get students thinking about the way they learn.

There are also some general principles about learning that are supported by research that we can pass along to students (informally, no lesson required). One is “distributed learning” (aka the spacing effect), meaning that learning is much more effective when studying is broken into smaller chunks over time than when crammed. This is especially helpful for students who have attention difficulties and may feel frustrated or bad about their need to take breaks while studying—the research shows that this is actually a better way to learn!

While old adages about studying may have said “use a familiar and comfortable study spot,” studies have shown that learning is actually enhanced when the surrounding context is varied. This means that studying in different locations, listening to different music or a variety of background noise, and with any other environmental variations can actually be beneficial.

Another learning strategy shown to be extremely effective is testing or “retrieval practice.” After spending some time studying the material, it’s best to put it away and see if we can recall it. Retrieval practice can include a formal in class assessment, or a homework assignment, but quizzing ourselves or having someone else quiz us is a great learning strategy that is supported by many studies. In How We Learn, author Benedict Carrey summarizes what’s been learned from research on retrieval practice in a 1/3 to 2/3 rule: the fastest way to learn something is to spend 1/3 of your time memorizing it and 2/3 of your time reciting it from memory.

Testing is studying, of a different and powerful kind. —Benedict Carrey

I find it helpful to share these types of strategies with students whenever possible, since it can help them make their study time more efficient.

Here are some questions that I want my students to be asking themselves in order to become more conscious of their learning habits and strategies. I usually take them through these types of questions a couple of times initially, and then I just remind them to ask themselves periodically.

How did I learn about this topic initially (lecture/presentation, assigned reading, activity, research project, etc.)?

How actively did I participate in the initially learning? What grade would I give myself for my efforts? (paying close attention, taking notes, completing the task well, reading carefully, asking questions, etc. vs zoning out, doing the minimum, skimming/skipping the reading, letting others do the work, etc.)

How much did I learn (as a percentage of what I need to know or be able to do)? What grade would I give my current understanding of the topic?

Could I explain the topic thoroughly to someone who knows nothing about it? Could I show someone step by step how to solve this type of problem or complete this task successfully?

What methods usually work best for me to learn something new?

What tools, resources, and practices can I use to get my knowledge/skill set to 100% with this topic?

Here are some steps to take students through in order to help them evaluate their own understanding of a topic. These can be used in any subject area.

Identify the topic as specifically as possible.

State what we know, what we don’t know, and what we need to know, keeping in mind that as we proceed we may uncover more aspects of the topic that we don’t know about

Identify the learning method: lecture with slides? Assigned reading? Research project? Informational video? Etc.

identify other learning methods/tools/resources that might be helpful or have been helpful in the past: asking the teacher for help, asking a friend, watching a video online, reading more online, rewriting my notes, doing additional practice, etc

Evaluate how much we know now: 50%? 75%? 100%? Etc.

Repeat the steps until understanding is at or near 100%.

I think self-reflection is one of the most important practices that we can pass along to students. Becoming more reflective about our own learning habits and strategies, as well as taking ownership over our learning, is a lifelong skill with so many benefits. I’ve created a resource that can be used with students in grades 6+ in any subject area for this purpose. It has three different self-evaluations: pre-semester, pre-assessment (to be used at the end of a unit but prior to a unit test), and post-assessment (for students to reflect on their learning during the unit and their preparation for and performance on the unit test).

Click on the photo below to get this resource and please let me know what you think about teaching learning strategies and self-reflection about learning!

Language building involves forming as many connections in the brain as possible so that new words are understood in concert with other words, ideas, and even visual representations.

Read MoreAs someone in an “ally” position as opposed to a perceived authoritarian, I’ve also been able to gain some insight into students’ motivations, their perspectives on school, teachers, assignments, etc., and their perception of themselves as students.

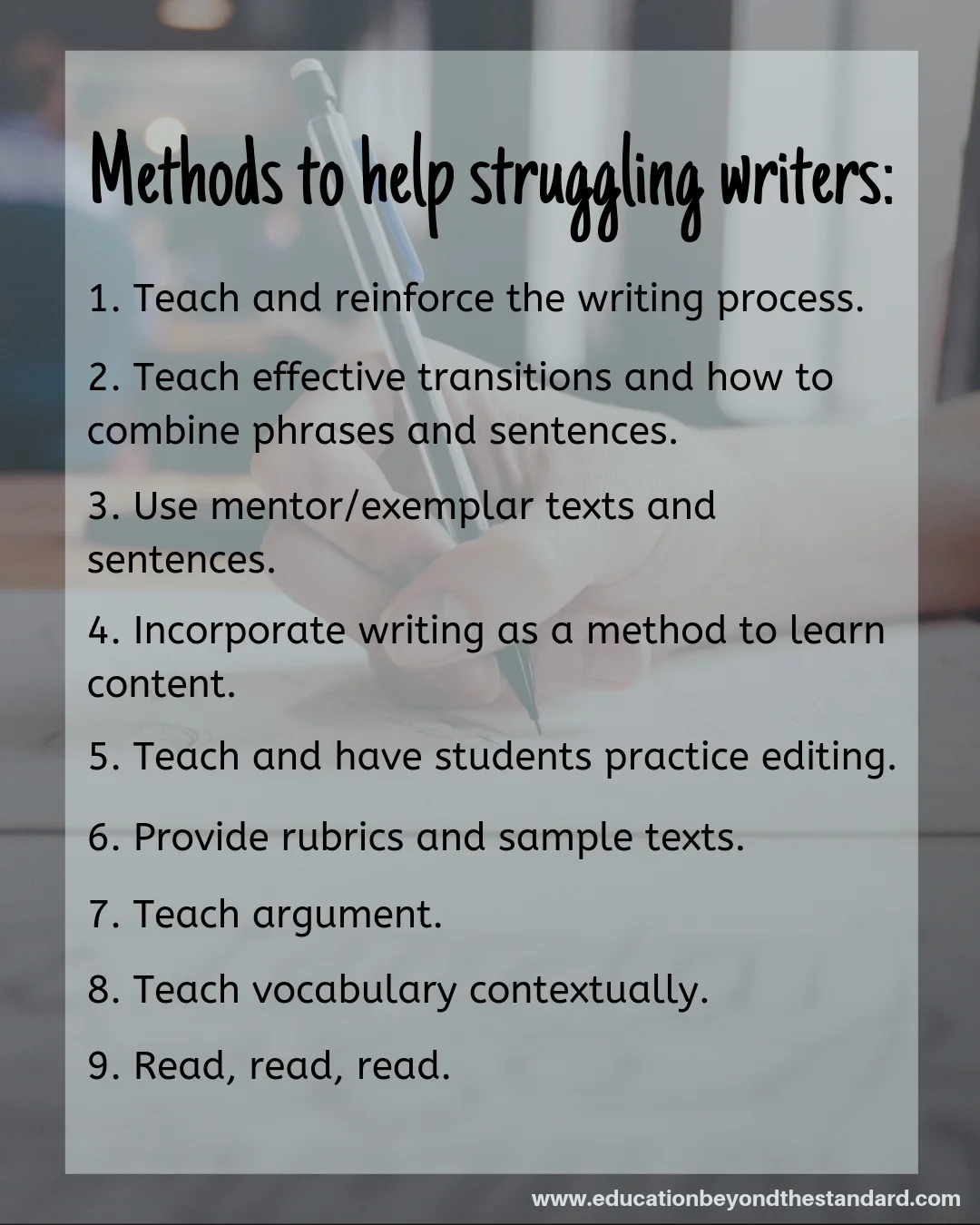

Read MoreIn a previous post, I talked about some of the similarities I’ve noticed in working with struggling writers. Now I’d like to share some methods for working with struggling writers that I’ve learned from personal experience and from the research on effective methods to improve student writing.

This point can’t be emphasized enough. While some stellar writers may instinctively use an effective writing process, the vast majority of our students will need specific instruction. Beyond teaching the steps of the writing process (Prewriting, Writing, Revising, Editing, Sharing), we need to teach students how to execute each step. And this requires practice.

Consider having students regularly outline essays in response to prompts in order to practice Prewriting. Make sure the outlines follow a logical structure and contain sufficient detail, as opposed to just brainstorming (which can be fine as an initial step in the Prewriting stage). Editing tasks and peer editing are good practice for editing and revising students’ own work.

Struggling writers often have difficulty putting together pieces of information (or arguments and supporting facts) in a logical and coherent way. Specific instruction on transition/linking words and phrases and how to use them is crucial to helping student writers.

Mentor texts and sentences illustrate the principles of writing and grammar that we’re teaching. Mentor sentences can be a great way to teach grammatical concepts and effective transitions. Also consider providing exemplar texts when you give a rubric (see below).

Writing about recently learned content has repeatedly been found effective in increasing retention and understanding. I’m a big believer in bringing writing activities into all subject areas, including math, science, and social studies.

Writing can be used across subject areas to:

reinforce content (“explain,” “summarize,” etc.),

make connections (“how is this material connected to [current events, something we learned previously]?” etc.), and

engage critical thinking (“why is this relevant/important?” “what else can we learn about this topic?” etc.).

Having tutored students in math for many years, I’ve noticed that when students can summarize or explain a process in writing they almost always achieve mastery with that topic. Incorporating writing wherever we can and across subject areas increases content understanding and provides even more opportunities for writing practice.

I can’t count the number of times I asked a student to edit his or her own draft, only to have the exact same draft returned to me with a few minor errors corrected. It took time for me to realize that many struggling writers don’t know intuitively how to edit their own work (or the work of others). Editing, just like writing, is a skill that must be taught. Students need to learn what to look for and how to look for it, as well as how to fix problems with sentences, paragraphs, or whole pieces of writing.

One of the best ways I’ve found to teach editing is by having students practice editing a text with defined numbers and categories of errors. By telling students how many errors there are within a certain category (like punctuation, verb tenses, etc.), we are training them to focus on the details that they otherwise may have skipped over. While zooming in to the grammatical details is important, we also need to teach students to zoom out to the big picture (the structure, strength of argument and supporting facts, etc.). Mentor texts are a great way to illustrate “big picture” qualities of writing.

One of the many great things I learned while tutoring students for the SAT/ACT was the value of sample texts in addition to a rubric. Many of the SAT/ACT study books contain sample student essays with a given score according to the general rubric provided. Reading a high-scoring essay and a low-scoring essay with the rubric as the backdrop is an impactful way for students to understand a grading rubric.

All too often, students eyes’ glaze over while reading rubric measures such as “arguments and supporting evidence are presented cohesively.” Providing sample essays on the highest and lowest end of the rubric and requiring students to read them (or even better, reviewing and discussing them in class) is a powerful tool to help students understand what constitutes a great piece of writing.

Argument and persuasion are often confused, but they are actually quite different. Argument can serve as persuasion, but persuasion requires much less in terms of reasoning. Argument is rooted in fact and logic while persuasion is rooted in opinion and emotion. Argument is essentially a truth-seeking endeavor, while persuasion is focused on, well, persuading.

I believe that we should prioritize teaching argument over persuasion, and that argument should be made a much bigger part of all school subjects. The process of argument (gathering evidence, making a claim, connecting the claim to the evidence, examining evidence to the contrary, and refining the claim accordingly) develops critical thinking and logical reasoning skills, which are part and parcel of thoughtful, coherent writing. These skills are also extremely important outside of academics.

While struggling writers often lack a broad vocabulary (or frequently misuse words), great writers tend to have great vocabulary and make effective word choices. Far beyond memorization of definitions, teaching vocabulary with a language building approach can have a great impact on students’ writing skills.

Vocabulary study with a language building approach is a holistic process that not only enriches students’ writing with greater variety of word choice, but also improves their grammar and their contextual understanding of language. Students learn words in context and practice using them correctly while also practicing good grammar. They learn to use different word forms (ex: meticulous, meticulously, meticulousness) while developing a better understanding of sentence structure.

Studies have consistently supported a correlation between increased reading and better writing skills. The same goes for the link between reading and vocabulary and other cognitive skills. There is no question that reading provides great intellectual and emotional benefits, so the more we can have students read the better.

Outside of assigned reading, here are some ideas for encouraging and incentivizing student reading:

1) give an optional reading list (during the year and/or over breaks) with prizes for completion

2) set up a “Twitter style reading board” where students add “tweets” about the books they’re reading

3) host a student book club or create small group book clubs that select a book and meet once a month

4) hold a class reading contest or class vs. class contest

5) give an optional reading list from which students choose several books and complete book projects

6) maintain a classroom library with a diverse selection of fiction and nonfiction

7) allow in-class reading of student selected books when students complete class work

8) create an Instagram-style board where students post photos inspired by what they’re reading with captions that relate the image to the text

9) hold a “books made into movies” seminar—students read/watch and discuss which version was better

I’d love to hear what methods you’ve found effective in helping students improve their writing skills!

The importance of good writing skills can’t be understated. While in some respects media and technology advances have changed the way we write (e.g., the prevalence of short statements as in tweets and social media captions, etc.), writing remains a fundamental form of human expression and transmission of ideas.

Despite educators’ best efforts, however, research indicates that a troubling percentage of students graduate from high school with poor writing skills and/or unprepared to write at a college level. Recent studies have shown that up to 3/4 of students across different grade levels lack proficiency in writing.

As teachers we know how difficult it can be to improve students’ writing skills. After all, there is so much that goes into good writing! And just as poor writing skills didn’t develop overnight, strong writing skills take time to develop.

Before looking at some research backed methods for helping students become better writers (in a separate post), I’d like to share some of the patterns and tendencies I’ve noticed in working with struggling writers over the years, both as a former classroom teacher and now tutor.

When asked to state the main idea of passage, describe its structure, analyze the development of an argument or theme, etc., struggling writers tend to give vague or unclear responses that are loosely supported by the text. It’s not surprising given that the same skills involved in good, logical, cohesive writing are required for analytical and critical reading. While reading and writing skills don’t go hand in hand 100% of the time, there is a large enough overlap that a weakness in one area typically predicts a weakness in the other.

These students may not be able to avoid using run-on sentences, for example, because they don’t actually understand what an independent clause/complete thought is. They might not understand on a fundamental level the role of the different parts of speech in a sentence. They might see that they’re getting marked off for the same things over and over again, but they aren’t able to make the connection and master the grammatical concepts involved.

These students tend not to read with an eye to detail and, as a result, they often miss all but the most glaring errors. Even when told that there are remaining punctuation issues, for example, they may be unable to find the errors.

It is often not obvious to struggling writers that the order of ideas has a huge impact on the coherence of a text. They tend to view ideas and information as discrete, somewhat related pieces rather than as part of an overall logical flow. When we point out a lack of logical sequencing or organization, they really don’t understand on a fundamental level why a particular sequence of thoughts makes more sense than another.

These students tend to have a limited working vocabulary, a poor understanding of the nuance and connotation differences between words, or both. They may be able to define a word but be unable to use it effectively in an appropriate context. They also tend to be repetitive in their word choice and unaware of redundancies in their writing. If asked to restate an idea in different words, for example, they often struggle to do so.

One of the biggest tendencies that I notice in the students who struggle with writing is that they usually don’t plan or outline their writing in advance. While some excellent writers can produce great essays without much advance planning, the majority of struggling writers start writing without an effective plan for organization and structure. They tend to resist the planning process unless it is made a mandatory part of the writing assignment (an outline required to be submitted, for example).

On the flip side, struggling writers may remain “stuck” in thinking about their writing assignments. They may have difficulty with writing fluency and knowing how to effectively start a piece of writing without significant prompting.

These students, more often than not, read very little, if anything, outside of what they’re assigned. With the prevalence of sites like Cliffnotes and Sparknotes, many reluctant readers scrape by without even reading assigned texts at all. (For better or worse, kids often tell me, their tutor, about the “shortcuts” they take.) They largely view reading as a task rather than a joy.

There are exceptions to all of the above, of course, and some struggling writers may have only one or two of these issues. In another post, I’ll address the methods I’ve found most effective in helping struggling writers.

Please let me know if you’ve noticed these or other issues with your struggling student writers!

Novel or nonfiction study is a great way to teach so many things: themes and symbolism, author’s craft and devices, literary analysis, and vocabulary too. But all too often, vocabulary gets relegated to a list with definitions that students memorize for a quiz or test...and likely forget soon after. Fortunately, it’s fairly easy to incorporate new vocabulary and language building activities into a novel or nonfiction study unit.

Read MoreMost kids (and adults) have dreams or ambitions of doing something. What often determines whether that something becomes reality is how we set ourselves up to achieve it. While of course some of our potential is influenced by what we get in the genetic lottery, a good portion of it is also the goals we set for ourselves and how effectively we direct our actions toward achieving those goals. It’s also influenced by how well we can work with our bad habits and replace them with good ones.

In short, effectively setting goals for ourselves and becoming more aware of our habits, good and bad, directly impacts the quality of our lives.

There’s no doubt that effective goal setting is a great lifelong skill, but there’s a lot of misunderstanding about how to set effective goals and the factors that influence whether they are achieved. While some learn good goal setting practices from parents, sports coaches, or music teachers, many of us get to adulthood without really knowing what good goal setting looks like. Imagine if we all learned about effective goal setting and habit change early in life!

I used to think of goal setting as one of those reflexive, automatic things that everyone knows how to do and does already. In my first year of classroom teaching I used to tell students, “set goals!” and think that was a meaningful piece of advice (sheesh). It hadn’t occurred to me that, for most of us, effective and meaningful goal setting doesn’t come naturally and needs to be learned.

As a tutor, I’ve realized that one of the most important tools I have to help students is to teach them effective goal setting. I’m now convinced that it’s something we should be actively teaching and reinforcing with all students.

Through effective goal setting, I’ve seen kids go from barely passing their classes to getting A’s and B’s and feeling good about school overall. I’ve also seen kids who had felt unmotivated and overwhelmed by school become focused and determined to achieve what they had set out to do. But it didn’t come from my telling them to “set goals.” It came from their understanding of what goals actually are and the specific steps needed to make goals into reality. It also came from their becoming more aware of their habits, good and bad, and how changing seemingly small habits is crucial to making bigger changes.

In order to help students become better goal setters, we need them to understand what effective goals look like, be able to break them into bite sized steps, and plan for any obstacles that may arise.

Meaningful goals are specific and measurable. The simplest way to think of this is whether the question “did you meet your goal?” can be answered with a simple yes or no. If not, the goal is not specific and measurable. Some goals may not lend themselves to setting a time limit, but when possible goals should include a completion time, like “tomorrow,” “for the semester,” etc. Once the time period passes, it should be easy to answer the question of whether the goal was achieved.

Next, goals need to be broken down into small and specific actions that are also measurable (yes/no). For example, if the goal is to complete a 10K run by the end of the month, the actions might consist of your weekly training schedule (week 1: run 2 miles 3x, etc.).

If the goal is academic (“get an A in History this semester”), the steps might be things like review my notes every day after school, turn in all my homework on time, keep a running vocabulary/terms list and update it at least weekly, etc. Like the goal itself, the steps must be specific and measurable in order to accurately assess their completion when reflecting back on the results of goal setting.

The next part is where people (especially yours truly) tend to fall down, unfortunately. Human nature is to procrastinate and avoid doing things that are less fun in favor of having fun. We think that by setting the intention to do something that we’ll be sure to do it, but as most of us probably know, it can be easier said than done.

We are also creatures of habit, and just as good habits can help us reach our goals, bad habits can make it more difficult for us to do so. Researcher and writer James Clear (check out his website here) writes that goals are like rudders, the things that give us direction, and systems are the oars, which actually get the work done. He also writes about the importance of habits in achieving goals, and specifically about how we can change our habits.

Effective goal setting requires consideration of the system that surrounds you. Too often, we set the right goals inside the wrong system. If you're fighting your system each day to make progress, then it's going to be really hard to make consistent progress.

There are all kinds of hidden forces that make our goals easier or harder to achieve. You need to align your environment with your ambitions if you wish to make progress for the long run.

—James Clear

By anticipating obstacles and challenges that may arise, we can prepare ourselves with a plan to complete our steps no matter what. This requires an honest evaluation of the types of challenges that may interfere with our achieving goals.

We can reflect on past experiences when we’ve set a goal and didn’t reach it for a number of reasons. We can also look at ways in which our environment can help us or hinder us in adopting the habits that help us meet our goals.

For example, I know that oftentimes I’ll get distracted with other projects or by texts or phone calls. So if I know I have to complete a step, I might plan to turn off my phone or put it far away until I finish. Or maybe I designate a specific time to complete the step so that nothing else can distract me.

I find it’s helpful for me to share with students some of my own obstacles and the ways that I deal with them in order to get them thinking about ways to better manage their obstacles.

After the goal’s time period has passed, it’s important for students to learn to reflect on what went wrong and what went right. This process helps them to better understand themselves and their strengths and weaknesses. It also encourages a growth mindset that is focused on progress and learning over perfection.

Reflecting on success or failure (and especially the process that led to either one) is also important in informing future goal setting. If we become aware that a bad habit prevented us from reaching a goal, we can work to overcome that habit and replace it with a better one.

If you’re interested in learning more about habit change, I recommend Atomic Habits by James Clear (Kindle version and audiobook), or you can listen to a great interview he did on The Psychology Podcast.

I’ve also created this no prep resource for teachers to bring goal setting into the classroom with a pre and post term goal setting activity.

Please let me know in the comments what you think about teaching goal setting, what works, what doesn’t, etc!

Powered by Squarespace.